Memories bob to the surface

Recalling the drowned hamlets of Scituate

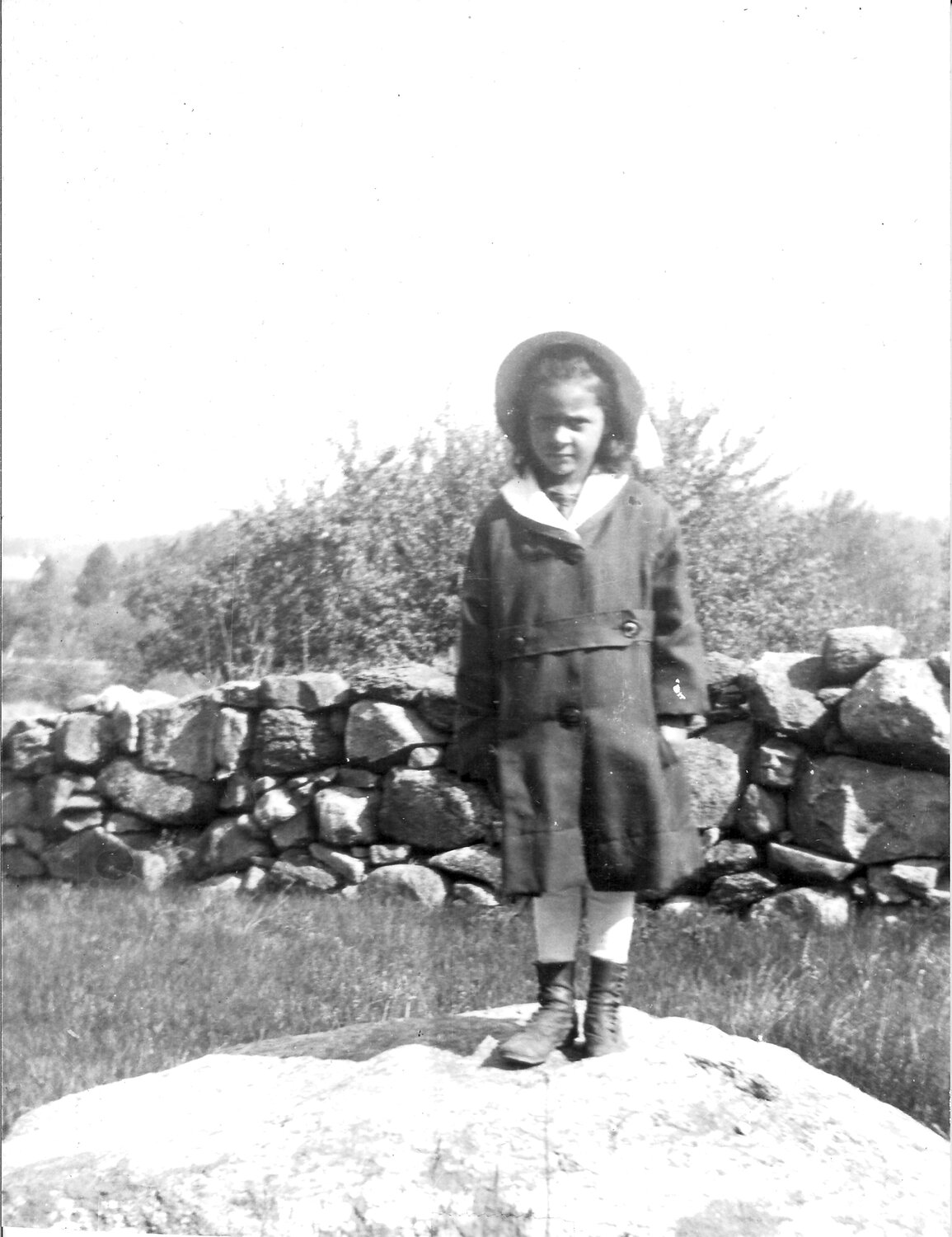

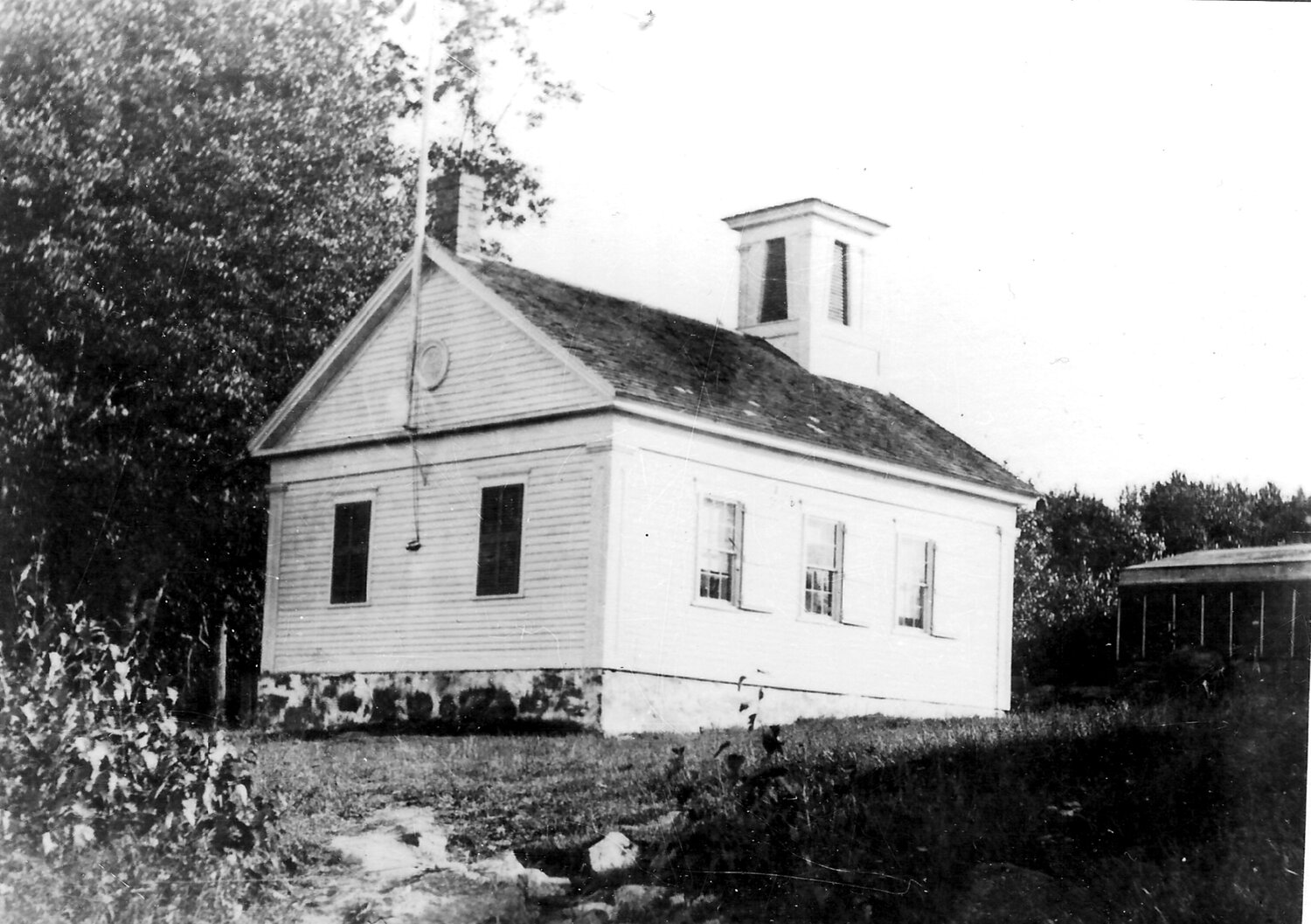

Helen O. Larson scrawled her first poem on the schoolhouse chalkboard as the building was dismantled.

About a century ago, someone bought Rockland’s school for $12, Larson told her son. It was torn down and carried away before the whole village was sunken underneath Rhode Island’s new reservoir.

“My mom used to tell me a lot of stories about her village getting torn down,” recalls Larson’s son, author Raymond A. Wolf. “Neighbors moving away, one at a time, never to be heard from again. They communicated via post card back then.”

But nearly everyone they knew would soon have a new address.

Rising Water

“On April 21, 1915 a public law was approved by the General Assembly to create the City of Providence Water Supply Board,” Wolf writes to begin his newest book, “The Lost Village of Rockland: Poems and Tales by Helen O. Larson.” “The board was given the power to condemn, by eminent domain, five villages in Rhode Island to build the Scituate Reservoir. They were: Ashland, Kent, Richmond, Rockland, and South Scituate.”

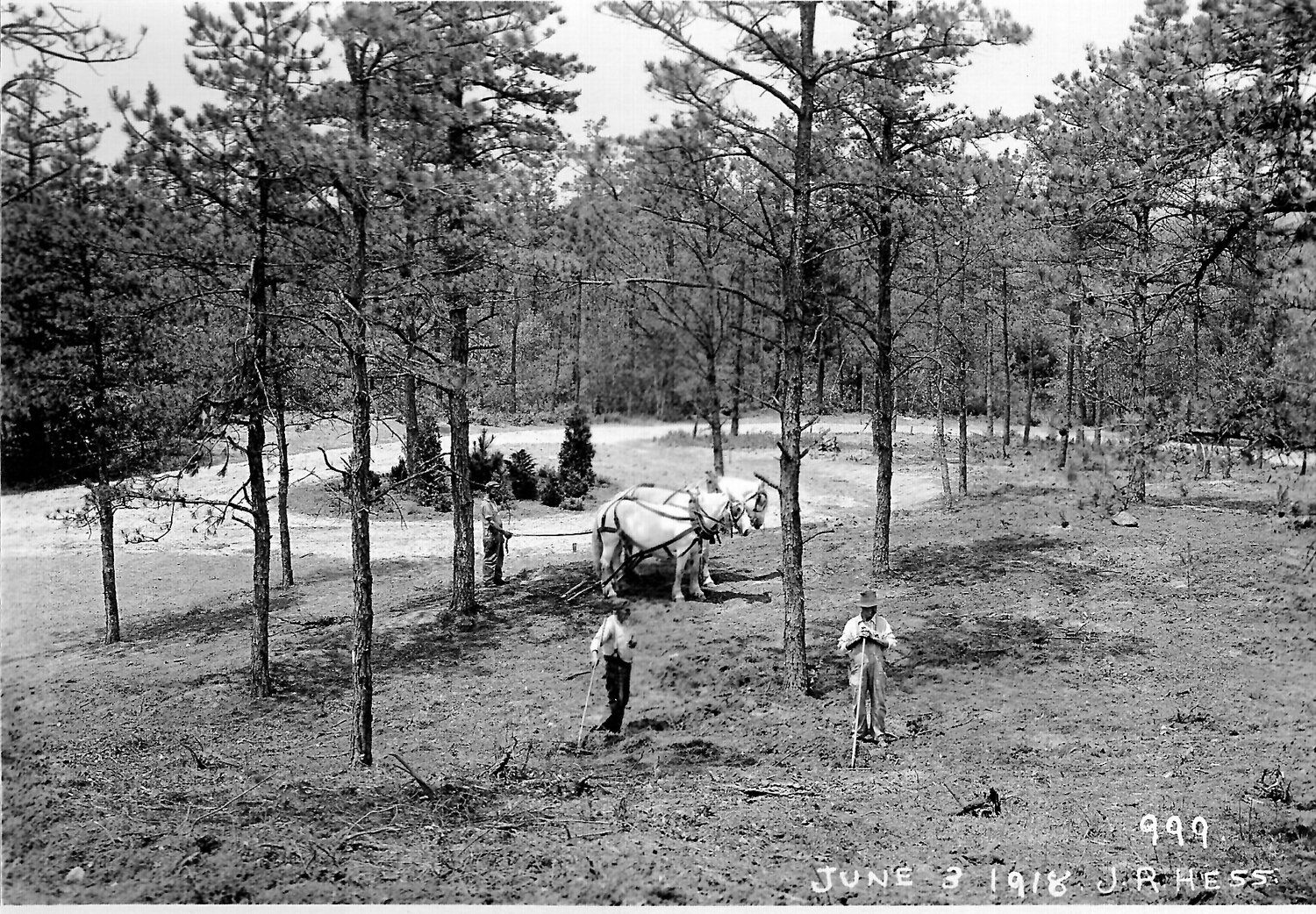

The government reclaimed nearly 15,000 acres.

“Because of the growth of Providence and a few extremely dry years the city was in bad need of more and clean water,” Wolf wrote in his book’s introduction. “Condemnation notices were sent out in December 1916 and the reservoir began storing water on Nov. 10, 1925.”

According to Wolf, the reservoir still “supplies water to 60 percent of Rhode Islanders.”

Mother Knew

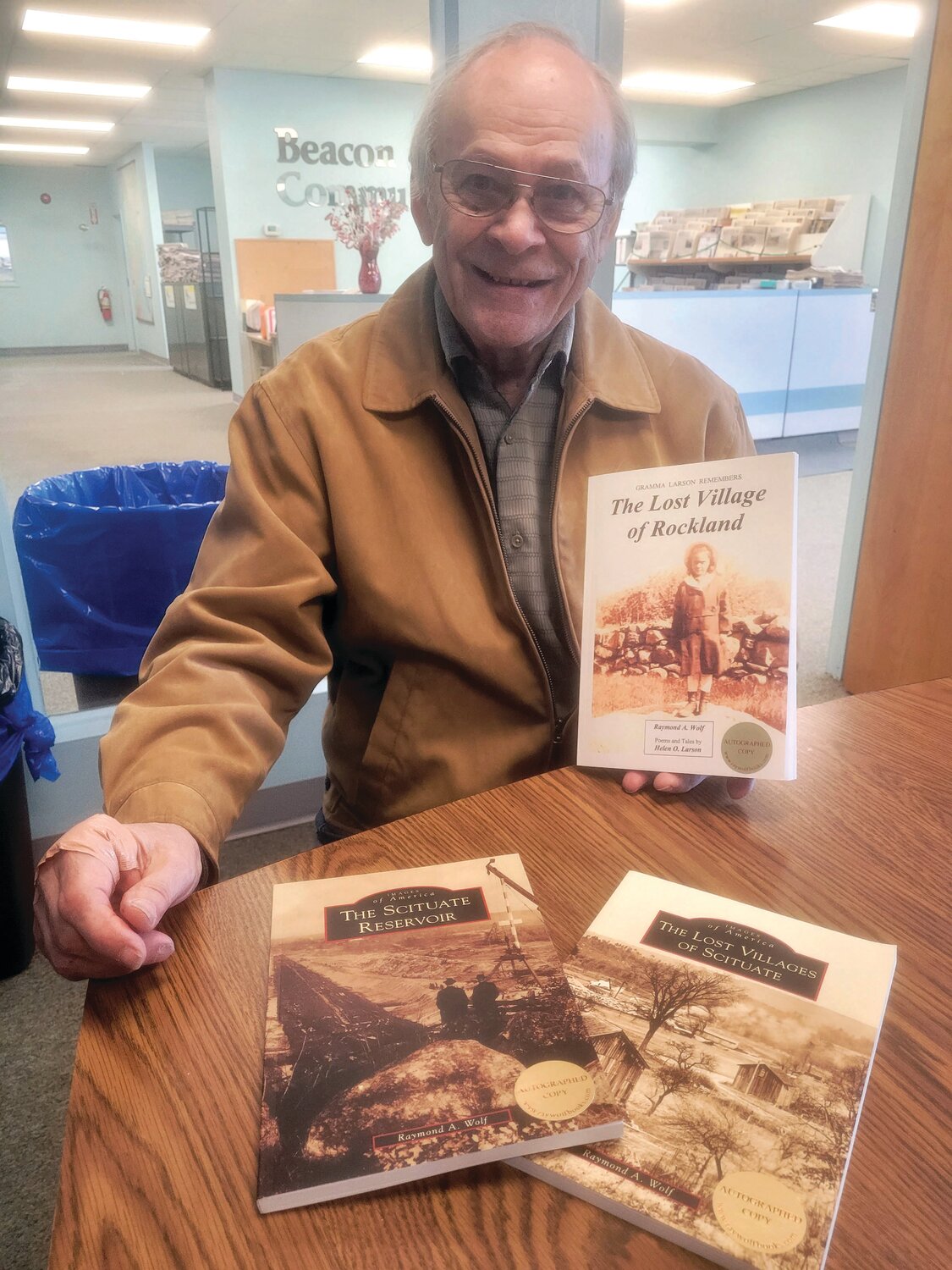

Wolf wanted to capture the voice of his mother, who he lost nearly 20 years ago. His new book mostly features her poetry, with historical photos from the village where she spent her earliest years.

“She tells her story of growing up in a small New England village in the early 1900s,” Wolf explains . “She writes about having to suffer the agony of seeing her village vanish. Through her poetry, she tells stories of her childhood and of the heartache she endured as each family moved away … The village was fated to be one of five that were destroyed. The buildings auctioned off one by one. Her friends’ and neighbors’ houses, the mill where her dad worked, the country store where she shopped for groceries for her mother, her beloved school and the church she attended every Sunday.”

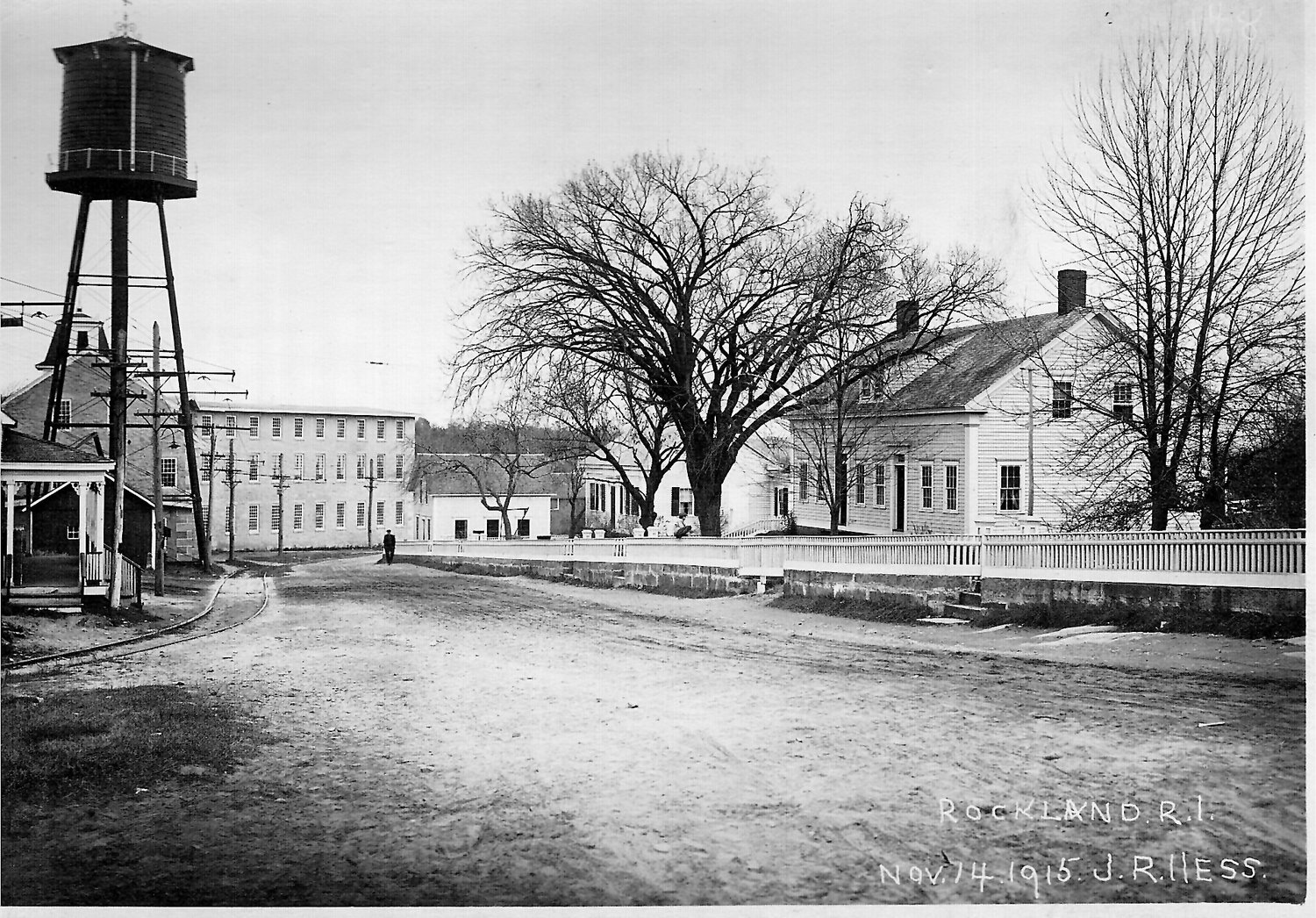

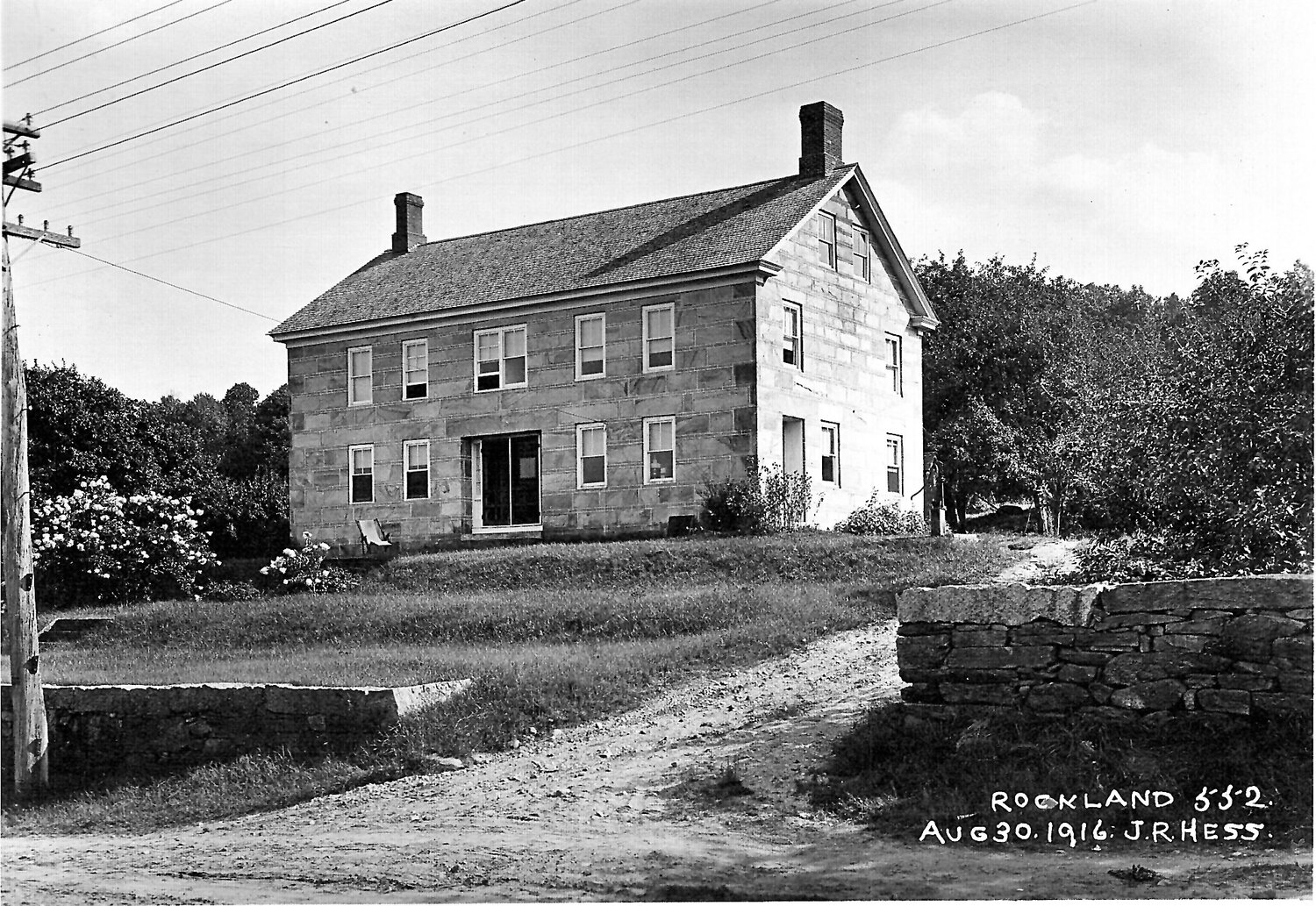

Rockland was the most bustling of the five drowned hamlets.

“Rockland had three mills, five stores — the post office was in one of them — two churches and two barbershops,” Wolf said, describing his mother’s hometown. “It was the largest village of the five; all the others had one mill, one store.”

The View

While his mother was still alive and writing, Wolf would get special permission from the Providence Water Supply Board to pass through a locked gate. He’d take his mother, and a lawn chair, to the water’s edge.

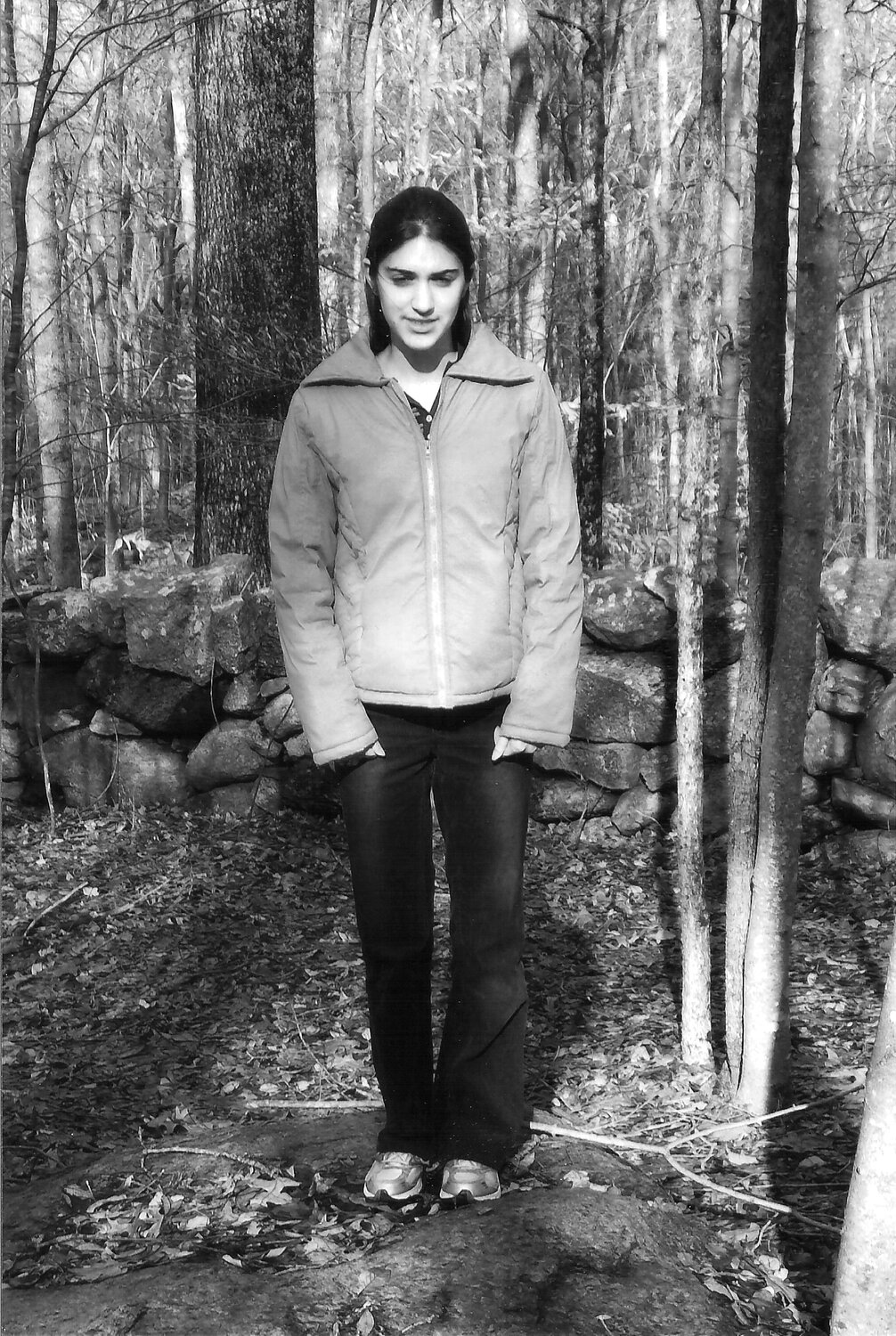

She’d sit and reflect on the lost towns, of which only the stone foundations and rock walls remain, nearly 40 feet below the water’s surface.

“I’d take my mom up there and she would point out where she used to play,” Wolf said.

He reflected on the Scituate Reservoir’s mirror surface.

“I see a village down there, just to the right of the causeway,” Wolf said. “I see cars driving around and horses. Cars coming down into the village, there, that one’s Ashland.”

He pictures his mother’s childhood village, “about 200-300 feet out in the water; 37 feet underneath the surface … and the stores, the post office, my mom’s house. All the houses were painted white.”

On a page opposite his mother’s portrait, circa 1940, Wolf shares the story of his mother’s first poem.

“She recalls the school house, that she loved, sold for only twelve dollars,” he wrote. “She wrote her first poem, The Old School House, on the blackboard as the workers were tearing it down. She was only twelve years old at the time but it was the beginning of a lifetime of writing poetry.”

Her inaugural poem, “The Old Schoolhouse,” is included inside Wolf’s new book.

Wolf’s family farm, perched upon a hill, survived, overlooking the reservoir’s massive footprint.